Yes, you should be angry about the housing crisis

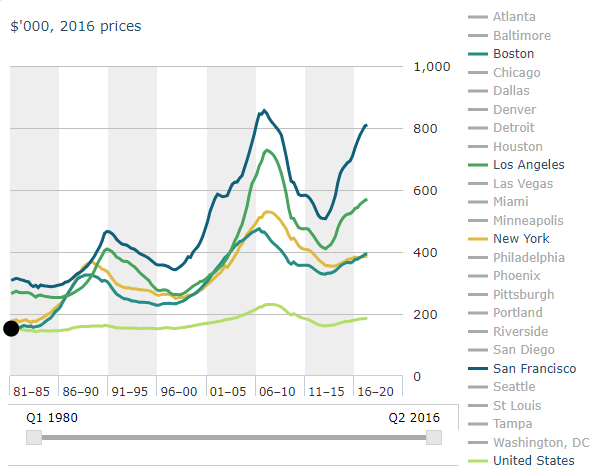

The easiest and most neglected way to make people in the developed world much better off is to fix housing policy. Record high property prices in thousands of major cities are burying people under crushing debt, crippling social mobility, and providing fuel for class divisions and xenophobia. And all of this could be easily avoided! I’ll explain how shortly (with particular reference to London and San Francisco, which are the examples I’m most familiar with, and which showcase widespread problems) but first let’s look at just how bad the crisis is (graphs from The Economist).

In Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the UK, average house prices have roughly tripled over the last 30 years. This is in real terms, adjusted for inflation; and it's in spite of whatever progress has occurred in construction techniques or materials. This is hundreds of thousands of dollars out of the average person's pocket, a vast and overwhelming expense.

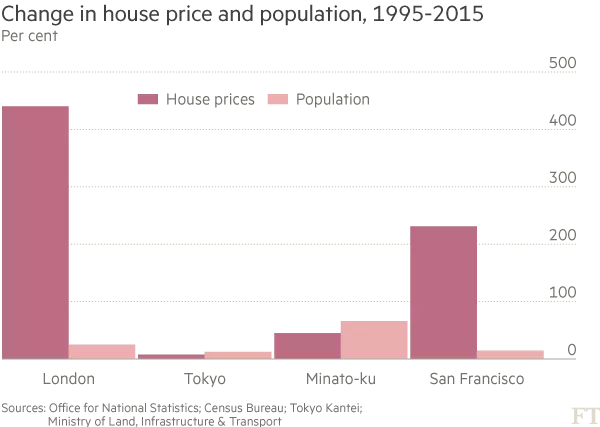

And it's even worse than that. Consider the trend in the US, where prices have "only" increased by 50%. Not so bad, right? But this is a national average. If we zoom in on the biggest cities, we see prices doubling in New York, Boston and Los Angeles, and multiplying by a factor of 2.5 in San Francisco. (Also, all this data is 2 years out of date; the problem's only gotten worse since then).

Similarly, Britain as a whole has seen prices increase to more than 3x their 1970 values- but in London specifically, prices are over 5x what they were back then. That's absurd, and has disastrous implications for the economy overall. Modern knowledge economies are built around network effects; that's why, within America, there’s overwhelming concentration of entrepreneurship in Silicon Valley, and finance in New York, and entertainment in Los Angeles. Cutting people off from them is the best way to slow down innovation - and that's exactly what housing prices are doing. Consider this study, which finds that around 75% of US growth over the last 50 years comes from only two dozen cities. Yet in places like New York, over half of that growth was eaten up by housing costs. In the authors’ (admittedly speculative) model, if even just three cities - New York, San Francisco, and San Jose - had kept their housing regulations at normal levels over the last 50 years, the average income across the entirety of America would be almost $9000 higher than it is today, with millions more people able to access good jobs.

It gets even worse! This isn't just a slow, long-term trend - it's accelerating. The sharpest increases have been specifically over the past two decades. You can see that in the graphs above, but it becomes even clearer if we look at longer-term data, like these Stockholm prices.

In other words: if you’re in my generation, this is your problem and mine. It was born around the same time we were, and it's going to shape our future. It stifles innovation, as people can't afford to move to places where the breakthroughs are happening. It pushes people into financial instability, living from rent payment to rent payment and only one missed paycheck away from disaster. (For a gripping account of the struggle poor families face in finding and keeping housing I recommend Evicted, a Pulitzer prizewinner). It's responsible for rises in homelessness in many major cities. And even for the lucky few who can afford to live in those hubs, it's a constant weight on our shoulders. (Note that rents are also increasing, but at a considerably slower rate than house prices overall. If you're okay with many more people becoming long-term renters, then the trends above are still very bad, but not disastrous. I discuss the relationship between rental and purchase prices in more detail later on.)

Okay, so what about those inherit a house, or manage to buy one? Won't they end up rich, as prices keep skyrocketing? Perhaps, but only at the expense of others: people who can't get enough capital for that initial purchase, and the next generation who will face even more crippling prices. Housing price increases don't generate wealth, they just transfer it, usually to those who are already better off. And what's more, it's not even a productive transfer. A "winner" from the house price lottery might end up living in a million-pound house, wishing they lived in one half as expensive and had the rest of their wealth in cash. But they can't get to that point unless they're willing to retire and move to the countryside, because every other house in their area will be just as expensive. Even their heirs won’t benefit from that wealth, since they’ll have to sink it into housing costs of their own.

Why?

The graph above is particularly striking to me because the only other graphs I've seen shaped like this are those cataloguing exponential increases in technology or population. Somehow, over the last twenty years, we've managed to create a similar trend which, instead of empowering progress and growth, has exactly the opposite effect. What's to blame?

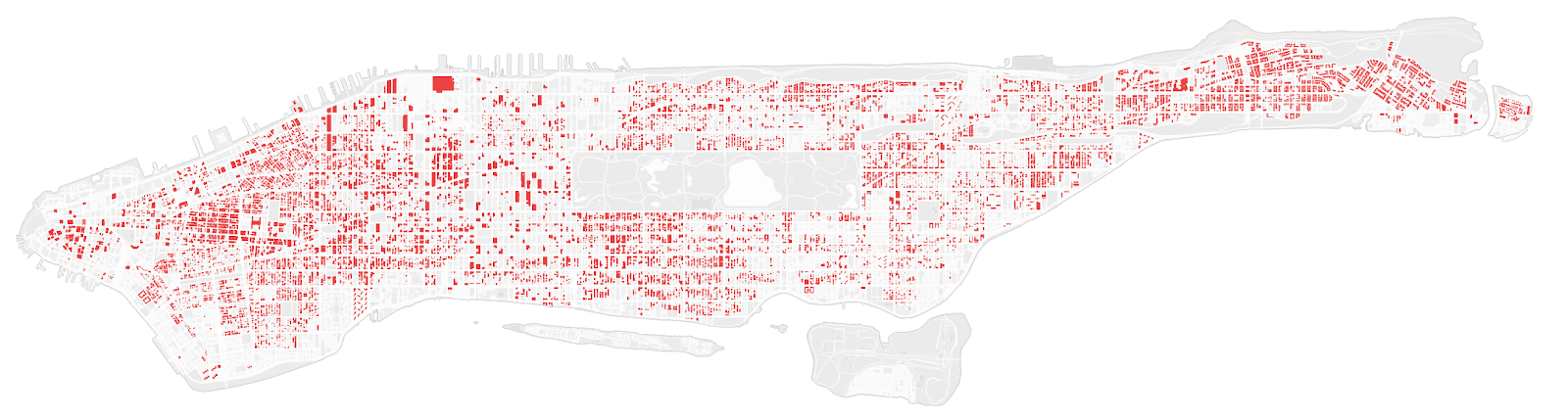

There are some subtleties on this issue, which I'll discuss shortly. But we simply cannot overlook the fact that the underlying cause of the spike in housing prices is government regulation, which severely curtails the supply of housing. The image above is a building plan of Manhattan - famous, of course, for its towering skyline. Most of those high-rises were built when the city's zoning code was relatively toothless. But boy has it expanded since then. How much? Well, the buildings marked in red are the ones that would be illegal to build today - 40% of the entire borough. What sort of problems do they have? Here are three common ones: they're too tall; they have too many apartments; or they have too many businesses. When governments strictly limit exactly the things which make buildings profitable and productive, it’s really not surprising that nobody’s building enough of them!

Height restrictions

Well, not quite nobody. Let's talk about height restrictions elsewhere. Here's Hong Kong, where they basically don't exist. Hong Kong is undergoing a housing crisis, but it’s perhaps the one place in the world which can’t fix it through increased construction, because they’ve already built about as much housing as is physically possible.

And here's London, which is just as wealthy a city, and is also currently undergoing a housing crisis, but seems much less inclined towards fixing it.

I'm not saying we should convert every building in London into a skyscraper. But right now there are only 1629 buildings in London that are taller than 35 metres or 12 stories. Moscow has over 7 times that many, and Seoul almost 10 times more (through some shocking coincidence, South Korea is one of the few developed countries where housing costs have actually decreased over the last 30 years, as shown in my first graph). Would doubling or tripling the figure really ruin London? Maybe it would make it slightly less pleasant. But would it make it half a million pounds per resident less pleasant? And even if you're willing to pay that price, what about the people who can't?

Land restrictions

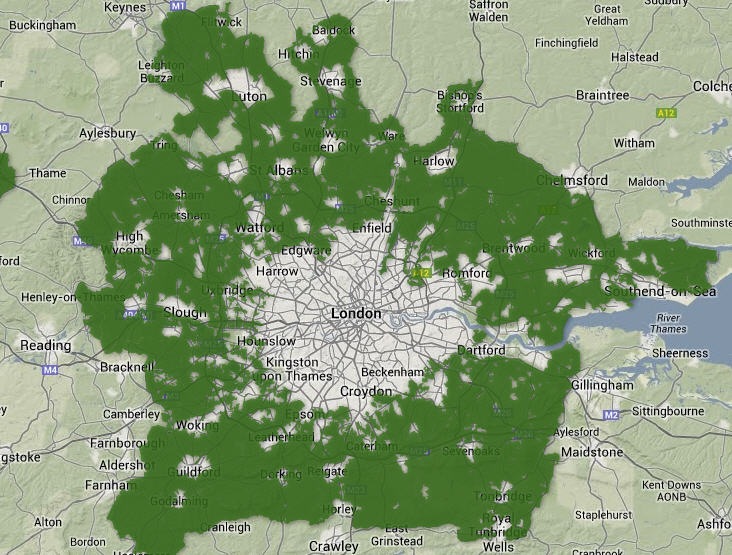

Perhaps the downsides of central housing restrictions would be mitigated if poorer people, who can’t afford the luxuries of nice views in central neighbourhoods at double the former price, were able to live further away and commute in. Unfortunately, that option has also been taken away from them. Here's London, surrounded as you can see by its "green belt", although in its effects it's more like a green noose. Building is severely restricted throughout this belt and others like it around many other UK cities. This means that people who can’t afford to live in the centre have to commute for an hour or more, on slow and expensive trains, from places like Reading. Increased commutes not only hit the poor the hardest but also increase energy use: the denser cities are, the fewer emissions per capita.

Unsurprisingly, these effects are quite far from the original aims of the green belt policy:

Isn’t the third goal on the list above legitimate, at least? Isn't there a worry that the UK might run out of countryside, with so many of its citizens pursuing life in urban centres? If you ask people to guess how much of UK land is "densely built on", the average guess is 47%. The true figure is 0.1%. If we include "built on" land, we get all the way up to 6%. People's perceptions on this issue are phenomenally inaccurate. There is not and probably never will be any shortage of land in this country or any other (excepting a handful of city-states).

There is a shortage of land in many cities, though, fueled by these misperceptions and the green belts themselves. People are irrationally fond of green belts, but we can easily solve the land shortage without environmental damage. In fact, 37% of the green belt is actually intensively farmed agricultural land, which is actively harmful to the environment! By contrast, just 1% of green belt land could hold enough housing to meet demand for several decades. Yet even that much is politically unacceptable, because Britons have been seduced by the mere use of the word “green”. The result? Buying land makes up 70% of the cost of a new home in London, up from just 25% a few decades ago. And ironically enough, this makes it far more difficult and expensive to create green spaces near where Londoners actually live.

Supply vs demand

The fundamental problem is that too many people want to live in too few houses. There are two ways that such mismatches get resolved: either the supply increases or the demand decreases. I've talked above about why the supply is artificially constrained; so instead, basic economic theory says that the price must increase until demand drops significantly. There are other ways to decrease demand, of course - for example, making it more attractive to live in smaller cities, or improving public transport so that people can commute from further away. These aren't ideal solutions, but they're better than nothing. Instead, national and city governments across the US and UK have taken what might be the most moronic strategy possible: they've implemented policies which increase demand and decrease supply. Californian cities have widespread rent control, which limits the rate at which rent can increase. So people who otherwise wouldn't stay in the city are able to. But that feel-good story is outweighed by the other clear effects: more people are competing for the remaining housing stock, so its prices go up even further; and what's worse, construction is diverted from high-density apartments (which run the risk of being declared rent-controlled properties) to larger luxury developments. Meanwhile, the UK government has been rolling out zero-interest loans for first-time home buyers - which means that they'll bid more for houses than they would have otherwise, again increasing demand and driving prices up. We’ve seen these sort of policies fail spectacularly before - it was a similar desire to increase home ownership which motivated Bill Clinton when he pressured Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac into handing out subprime mortgages like candy, which led to a major housing bubble and subsequent global recession.

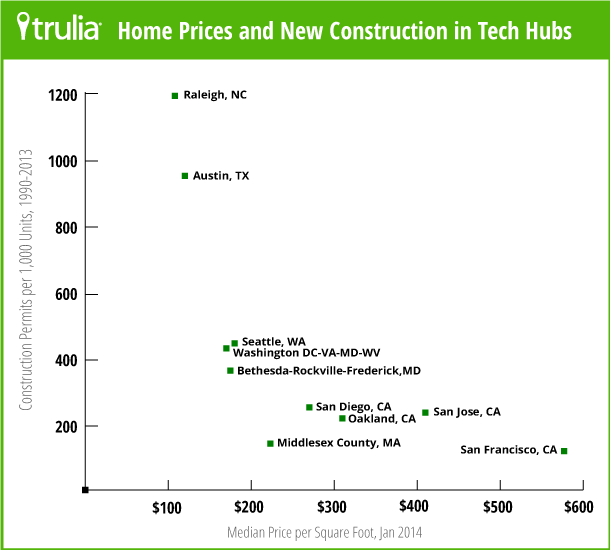

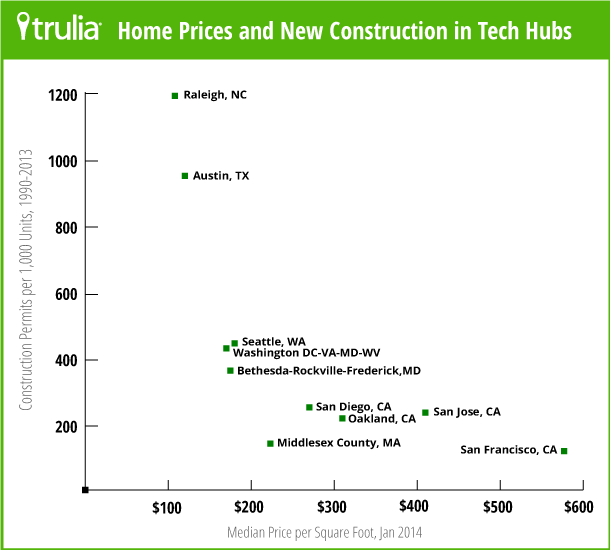

If you're not yet convinced that a lack of supply is the most important factor in rising house prices, consider the following graph (sourced from here) of house prices compared with the rate at which housing permits were issued in ten American tech hubs, showing a very clear negative correlation.

Misaligned incentives

It's not just outright stupidity which is behind the housing crisis, but also clashes of interests. Local homeowners often block development in their area (the catch-all term for such opposition is NIMBYism: Not In My Back Yard). It's often said that NIMBY groups are mainly trying to protect their own home prices, but I'm not convinced that's true - if you live in a central neighbourhood that suddenly allows the construction of skyscrapers, your land's value will soar (at least until everyone else follows suit). Instead, I'd guess, NIMBYism is about less quantifiable issues like the "character of the community". At its best, this may be aimed at maintaining social capital and cohesion; but at its worst it can be a way to express racist or classist sentiments. Either way, the overall trend is regressive because even if it benefits property owners, it harms younger and poorer people, who are much less likely to own houses. It also cuts away at social mobility, because it takes much more capital to move to places where the opportunities are. Inter-state migration within the US has fallen sharply over the last few decades, as younger workers are faced with job and housing markets dominated by an ageing population. Some YIMBY (Yes In My Back Yard) groups are doing good work against NIMBYism, particularly in California, but they don't yet have much traction by comparison (although kudos to Stripe, who recently donated $1,000,000; I think other tech companies are also starting to do serious advocacy).

Other regulatory issues

In Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the UK, average house prices have roughly tripled over the last 30 years. This is in real terms, adjusted for inflation; and it's in spite of whatever progress has occurred in construction techniques or materials. This is hundreds of thousands of dollars out of the average person's pocket, a vast and overwhelming expense.

And it's even worse than that. Consider the trend in the US, where prices have "only" increased by 50%. Not so bad, right? But this is a national average. If we zoom in on the biggest cities, we see prices doubling in New York, Boston and Los Angeles, and multiplying by a factor of 2.5 in San Francisco. (Also, all this data is 2 years out of date; the problem's only gotten worse since then).

Similarly, Britain as a whole has seen prices increase to more than 3x their 1970 values- but in London specifically, prices are over 5x what they were back then. That's absurd, and has disastrous implications for the economy overall. Modern knowledge economies are built around network effects; that's why, within America, there’s overwhelming concentration of entrepreneurship in Silicon Valley, and finance in New York, and entertainment in Los Angeles. Cutting people off from them is the best way to slow down innovation - and that's exactly what housing prices are doing. Consider this study, which finds that around 75% of US growth over the last 50 years comes from only two dozen cities. Yet in places like New York, over half of that growth was eaten up by housing costs. In the authors’ (admittedly speculative) model, if even just three cities - New York, San Francisco, and San Jose - had kept their housing regulations at normal levels over the last 50 years, the average income across the entirety of America would be almost $9000 higher than it is today, with millions more people able to access good jobs.

It gets even worse! This isn't just a slow, long-term trend - it's accelerating. The sharpest increases have been specifically over the past two decades. You can see that in the graphs above, but it becomes even clearer if we look at longer-term data, like these Stockholm prices.

In other words: if you’re in my generation, this is your problem and mine. It was born around the same time we were, and it's going to shape our future. It stifles innovation, as people can't afford to move to places where the breakthroughs are happening. It pushes people into financial instability, living from rent payment to rent payment and only one missed paycheck away from disaster. (For a gripping account of the struggle poor families face in finding and keeping housing I recommend Evicted, a Pulitzer prizewinner). It's responsible for rises in homelessness in many major cities. And even for the lucky few who can afford to live in those hubs, it's a constant weight on our shoulders. (Note that rents are also increasing, but at a considerably slower rate than house prices overall. If you're okay with many more people becoming long-term renters, then the trends above are still very bad, but not disastrous. I discuss the relationship between rental and purchase prices in more detail later on.)

Okay, so what about those inherit a house, or manage to buy one? Won't they end up rich, as prices keep skyrocketing? Perhaps, but only at the expense of others: people who can't get enough capital for that initial purchase, and the next generation who will face even more crippling prices. Housing price increases don't generate wealth, they just transfer it, usually to those who are already better off. And what's more, it's not even a productive transfer. A "winner" from the house price lottery might end up living in a million-pound house, wishing they lived in one half as expensive and had the rest of their wealth in cash. But they can't get to that point unless they're willing to retire and move to the countryside, because every other house in their area will be just as expensive. Even their heirs won’t benefit from that wealth, since they’ll have to sink it into housing costs of their own.

Why?

The graph above is particularly striking to me because the only other graphs I've seen shaped like this are those cataloguing exponential increases in technology or population. Somehow, over the last twenty years, we've managed to create a similar trend which, instead of empowering progress and growth, has exactly the opposite effect. What's to blame?

There are some subtleties on this issue, which I'll discuss shortly. But we simply cannot overlook the fact that the underlying cause of the spike in housing prices is government regulation, which severely curtails the supply of housing. The image above is a building plan of Manhattan - famous, of course, for its towering skyline. Most of those high-rises were built when the city's zoning code was relatively toothless. But boy has it expanded since then. How much? Well, the buildings marked in red are the ones that would be illegal to build today - 40% of the entire borough. What sort of problems do they have? Here are three common ones: they're too tall; they have too many apartments; or they have too many businesses. When governments strictly limit exactly the things which make buildings profitable and productive, it’s really not surprising that nobody’s building enough of them!

Height restrictions

Well, not quite nobody. Let's talk about height restrictions elsewhere. Here's Hong Kong, where they basically don't exist. Hong Kong is undergoing a housing crisis, but it’s perhaps the one place in the world which can’t fix it through increased construction, because they’ve already built about as much housing as is physically possible.

And here's London, which is just as wealthy a city, and is also currently undergoing a housing crisis, but seems much less inclined towards fixing it.

I'm not saying we should convert every building in London into a skyscraper. But right now there are only 1629 buildings in London that are taller than 35 metres or 12 stories. Moscow has over 7 times that many, and Seoul almost 10 times more (through some shocking coincidence, South Korea is one of the few developed countries where housing costs have actually decreased over the last 30 years, as shown in my first graph). Would doubling or tripling the figure really ruin London? Maybe it would make it slightly less pleasant. But would it make it half a million pounds per resident less pleasant? And even if you're willing to pay that price, what about the people who can't?

Land restrictions

Perhaps the downsides of central housing restrictions would be mitigated if poorer people, who can’t afford the luxuries of nice views in central neighbourhoods at double the former price, were able to live further away and commute in. Unfortunately, that option has also been taken away from them. Here's London, surrounded as you can see by its "green belt", although in its effects it's more like a green noose. Building is severely restricted throughout this belt and others like it around many other UK cities. This means that people who can’t afford to live in the centre have to commute for an hour or more, on slow and expensive trains, from places like Reading. Increased commutes not only hit the poor the hardest but also increase energy use: the denser cities are, the fewer emissions per capita.

Unsurprisingly, these effects are quite far from the original aims of the green belt policy:

- To check the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas

- To prevent neighbouring towns from merging into one another

- To assist in safeguarding the countryside from encroachment

- To preserve the setting and special character of historic towns

- To assist in urban regeneration, by encouraging the recycling of derelict and other urban land

Isn’t the third goal on the list above legitimate, at least? Isn't there a worry that the UK might run out of countryside, with so many of its citizens pursuing life in urban centres? If you ask people to guess how much of UK land is "densely built on", the average guess is 47%. The true figure is 0.1%. If we include "built on" land, we get all the way up to 6%. People's perceptions on this issue are phenomenally inaccurate. There is not and probably never will be any shortage of land in this country or any other (excepting a handful of city-states).

There is a shortage of land in many cities, though, fueled by these misperceptions and the green belts themselves. People are irrationally fond of green belts, but we can easily solve the land shortage without environmental damage. In fact, 37% of the green belt is actually intensively farmed agricultural land, which is actively harmful to the environment! By contrast, just 1% of green belt land could hold enough housing to meet demand for several decades. Yet even that much is politically unacceptable, because Britons have been seduced by the mere use of the word “green”. The result? Buying land makes up 70% of the cost of a new home in London, up from just 25% a few decades ago. And ironically enough, this makes it far more difficult and expensive to create green spaces near where Londoners actually live.

Supply vs demand

The fundamental problem is that too many people want to live in too few houses. There are two ways that such mismatches get resolved: either the supply increases or the demand decreases. I've talked above about why the supply is artificially constrained; so instead, basic economic theory says that the price must increase until demand drops significantly. There are other ways to decrease demand, of course - for example, making it more attractive to live in smaller cities, or improving public transport so that people can commute from further away. These aren't ideal solutions, but they're better than nothing. Instead, national and city governments across the US and UK have taken what might be the most moronic strategy possible: they've implemented policies which increase demand and decrease supply. Californian cities have widespread rent control, which limits the rate at which rent can increase. So people who otherwise wouldn't stay in the city are able to. But that feel-good story is outweighed by the other clear effects: more people are competing for the remaining housing stock, so its prices go up even further; and what's worse, construction is diverted from high-density apartments (which run the risk of being declared rent-controlled properties) to larger luxury developments. Meanwhile, the UK government has been rolling out zero-interest loans for first-time home buyers - which means that they'll bid more for houses than they would have otherwise, again increasing demand and driving prices up. We’ve seen these sort of policies fail spectacularly before - it was a similar desire to increase home ownership which motivated Bill Clinton when he pressured Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac into handing out subprime mortgages like candy, which led to a major housing bubble and subsequent global recession.

If you're not yet convinced that a lack of supply is the most important factor in rising house prices, consider the following graph (sourced from here) of house prices compared with the rate at which housing permits were issued in ten American tech hubs, showing a very clear negative correlation.

Misaligned incentives

It's not just outright stupidity which is behind the housing crisis, but also clashes of interests. Local homeowners often block development in their area (the catch-all term for such opposition is NIMBYism: Not In My Back Yard). It's often said that NIMBY groups are mainly trying to protect their own home prices, but I'm not convinced that's true - if you live in a central neighbourhood that suddenly allows the construction of skyscrapers, your land's value will soar (at least until everyone else follows suit). Instead, I'd guess, NIMBYism is about less quantifiable issues like the "character of the community". At its best, this may be aimed at maintaining social capital and cohesion; but at its worst it can be a way to express racist or classist sentiments. Either way, the overall trend is regressive because even if it benefits property owners, it harms younger and poorer people, who are much less likely to own houses. It also cuts away at social mobility, because it takes much more capital to move to places where the opportunities are. Inter-state migration within the US has fallen sharply over the last few decades, as younger workers are faced with job and housing markets dominated by an ageing population. Some YIMBY (Yes In My Back Yard) groups are doing good work against NIMBYism, particularly in California, but they don't yet have much traction by comparison (although kudos to Stripe, who recently donated $1,000,000; I think other tech companies are also starting to do serious advocacy).

Other regulatory issues

- Slow and bureaucratic planning permission processes. From this paper on San Francisco:

- There was only one factor on which all interviewees and focus group participants agreed: the most significant and pointless factor driving up construction costs was the length of time it takes for a project to get through the city permitting and development processes… Participants noted that “additional hoops and requirements seem to pop up at various stages in the process” and that projects are subject to “re-interpretation of the codes throughout the permitting process.”... Another challenge is the frequency of appeals on projects, including affordable or workforce housing units. In San Francisco, every permit is appealable; since very few large-scale projects match the city’s existing building and planning codes, this translates into numerous opportunities for appeals and contributes to delays in the entitlement process. Focus group participants noted that a large percent of appeals are eventually denied, meaning that the time spent on the appeal does not typically produce different outcomes other than increasing the time and cost in pre-construction. “There’s no benefit to the public – the need to get ‘exceptions’ approved just adds costs.”

- Protected views. There are 13 protected views of St Paul's Cathedral, the Palace of Westminster and the White Tower, which mean that tall buildings are prohibited along a series of lines which criss-cross London. In Edinburgh, there are 170 protected views; this is also a serious problem in San Francisco.

- Protection of historic buildings, of which there are 377,587 across England. History is important, but that's an absurdly high number. Having a building listed as historic can be such a financial blow that the government also offers Certificates of Immunity from listing. Presumably the buildings they're protecting are actually important, at least? Well, in San Francisco a proposal to replace a laundromat with 75 housing units, which had already been delayed for several years getting permits, is now at risk of being cancelled because several charities used to meet in the building in the 70s - even though there's no trace of them left. (One of the charities was focused on making housing more affordable, a stroke of irony you really couldn't make up). Also, there's no good way to get a building off the list, since it's practically tautological that buildings become more historic over time (the UK website suggests that they might consider doing so if the building has literally burned down).

- Mandatory parking requirements and very cheap street parking essentially force people to pay for driving facilities they don't even use. Fortunately, London abolished the former in 2004 - and saw the number of private carparks built halve, showing that people simply didn't want to pay for more parking. Which is not surprising, considering that each above-ground parking space costs around $25000, and each underground one costs around $35000. Meeting Los Angeles' minimum requirement for parking spaces increases the cost of building a new shopping centre there by around 60 to 90%! That's assuming it's even possible - if not, the development would need to be cancelled entirely.

- Zoning, which is particularly bad in the US, and contributes to urban deserts and the need to drive everywhere. The Reserve Bank of Australia estimates that “zoning raised detached house prices 73% above marginal costs in Sydney and 69% in Melbourne”.

- Lots and lots of other miscellaneous crap - like California's new law that requires solar panels on the roof of every new building, despite the fact that they're much less efficient and much more expensive than industrial installations; or Austrian villages where, by law, every house must be a picturesque 19th-century-style cottage; or Oxford, where no building is allowed to be taller than Carfax Tower (i.e. four stories); or...

Other possible causes

Overall, I think that by cutting regulation, we could build much, much more housing than we currently do, and make it much more affordable than it currently is, and that would be a very good thing. Although this is the consensus amongst economists, it hasn’t been particularly popular politically. A number of alternative causes of our housing crises are often thrown around, some of which have merit and some of which don't. Let's have a look at them:

Case closed? I don't think so, few a few reasons. Firstly, there are many cities in which rents have increased drastically: the cost of rent in New York as a percentage of national median income has gone from 10% in 1950 to over 80% now. Given this, I'm somewhat suspicious of the London data. Compare, for instance, the next graph, which paints a contradictory picture, showing a 23% rise since 2011 alone.

Secondly, I don't see any good reason why housing costs should be measured as a percentage of income, rather than in real terms. If you account for increasing incomes, the chart above actually shows housing in London becoming 40% more expensive over the last two decades. If that happened for any other life essential, like food, people would consider it a scandal regardless of whether incomes had increased as well.

More importantly, even if interest rates drove house prices up in the first place, the natural response is for more construction to drive prices down again. This is simple supply and demand - given higher prices, construction firms can expand their activities and make more profit. Since that hasn't happened, something must be preventing them from doing so. I suggest that the factors I outlined above are responsible both for the rise in rental prices and for the vulnerability of the housing market to changes in interest rates. There are some reasons to think that more people renting is a good thing, because it allows them to be more flexible and mobile. But people seem to have a strong revealed preference for owning their own houses, and so are disincentivised from moving to the places with high productivity and high house prices, which undermines the whole point of increasing mobility. Pro-homeowning attitudes also benefit the economy overall by increasing saving and building stronger communities. So I do think that pushing people into renting is a significant harm, one which is further exacerbated by recent increases in rents.

Overall, I think that by cutting regulation, we could build much, much more housing than we currently do, and make it much more affordable than it currently is, and that would be a very good thing. Although this is the consensus amongst economists, it hasn’t been particularly popular politically. A number of alternative causes of our housing crises are often thrown around, some of which have merit and some of which don't. Let's have a look at them:

- Interest rates

Case closed? I don't think so, few a few reasons. Firstly, there are many cities in which rents have increased drastically: the cost of rent in New York as a percentage of national median income has gone from 10% in 1950 to over 80% now. Given this, I'm somewhat suspicious of the London data. Compare, for instance, the next graph, which paints a contradictory picture, showing a 23% rise since 2011 alone.

Secondly, I don't see any good reason why housing costs should be measured as a percentage of income, rather than in real terms. If you account for increasing incomes, the chart above actually shows housing in London becoming 40% more expensive over the last two decades. If that happened for any other life essential, like food, people would consider it a scandal regardless of whether incomes had increased as well.

More importantly, even if interest rates drove house prices up in the first place, the natural response is for more construction to drive prices down again. This is simple supply and demand - given higher prices, construction firms can expand their activities and make more profit. Since that hasn't happened, something must be preventing them from doing so. I suggest that the factors I outlined above are responsible both for the rise in rental prices and for the vulnerability of the housing market to changes in interest rates. There are some reasons to think that more people renting is a good thing, because it allows them to be more flexible and mobile. But people seem to have a strong revealed preference for owning their own houses, and so are disincentivised from moving to the places with high productivity and high house prices, which undermines the whole point of increasing mobility. Pro-homeowning attitudes also benefit the economy overall by increasing saving and building stronger communities. So I do think that pushing people into renting is a significant harm, one which is further exacerbated by recent increases in rents.

- Developers only building for the wealthy

This is less of a problem than it sounds because whenever developers build new housing for the wealthy, it means that they no longer occupy other accommodation, which allows middle-class people to move in, which frees up other accommodation, and so on... And in fact the luxury housing of 20 years ago often becomes the ordinary housing of today. But there is a valid underlying concern, which is that luxury units aren't very high-density, and so they’re not a particularly good use of desirable central land. So why are they being built? Well, if you raise the costs of development by making it more difficult to get planning permission and more expensive to build large numbers of apartments, then the rational response for developers is to focus on projects with higher margins, i.e. luxury accommodation or office spaces. Mandatory parking minimums showcase this point well - if you have to allow for one parking space per apartment even though the market won't cover that cost, then by making each apartment bigger, and building fewer of them, you lose less money on parking (rent controls have a similar effect, as I outlined above). The best way to get more cheap housing is simply to make construction cheaper, and the best way to do that is still by decreasing regulation.

- Cuts to government homebuilding

- Foreign investment

There's often populist outrage about foreigners buying properties only to leave them empty. Londoners blame Russian oligarchs; Aucklanders blame the Chinese. Firstly, we should recognise that the number of properties involved is pretty small. But more importantly, we should think of this as a golden opportunity. It's good for domestic companies to be able to sell goods overseas, right? Well, because of our countries' various advantages, such as stability and the rule of law, foreigners are willing to buy certain products that only we can manufacture - namely, houses in our cities - at high prices. And the gain from this sale is a lasting one, because such investors are still paying property taxes, but not using any local services! If housing were something with a small fixed supply, then perhaps we should be worried. But I've already argued that even in big cities like London, housing is scarce not for intrinsic reasons, but rather because of regulatory restrictions. Cutting off foreign investors might ease the housing crisis temporarily, but in the long term it's just depriving ourselves of a valuable source of income.

Some argue instead that improving transport isn't a substitute for increasing housing density, but a prerequisite for it, because otherwise transport systems will be overwhelmed. I don't know enough about transport infrastructure to evaluate this thoroughly, but it seems odd to me because if people live further away and commute in to city centers, that surely creates even more congestion, especially at peak hours. Living centrally allows more sustainable alternatives like biking or bussing - and with increased wealth from bigger populations, central city governments will have more money to sink into capital-intensive forms of transport like trains and metros.

Other effects

So far, I've mainly talked about the financial and economic harms of the housing crisis. But because housing is such a foundational part of our lives, it also has flow-on effects in many areas.

For example, housing startup Zillow found that over the last five years, the average age of first-time home buyers in the US rose by 2.7 years. This is an incredibly sharp increase which turns out to be correlated with a significant decrease in birth rates. That is, the more house prices in an area increase, the fewer children its residents have. While this relationship hasn't been proved to be causal, it suggests that house prices are disrupting people's ability to even have the types of families they desire.

Another metric which has been rising is commuting time, as people need to live further and further away from city centres. Unsurprisingly, this turns out to be strongly correlated with unhappiness and anxiety. People with long commutes are less satisfied with their lives and feel like their daily activities are less worthwhile.

What else affects happiness? Possibly the biggest single factor is quality of social relationships. With higher housing prices, though, it's more difficult to find accommodation near your friends, because you're all much more financially constrained. Increases in the proportion of people renting are also detrimental to relationships: because they move around frequently, renters find it harder to build up deep ties with neighbourhood communities. These are likely factors driving the current loneliness epidemic.

Lastly, you may have heard of Piketty's book Capital in the 21st Century, which argues that the returns to capital are increasing, leading to the rise of a new rentier class at the expense of workers. But this reanalysis argues that when depreciation is accounted for, the only type of capital whose returns are rising is housing! So any discussion of rising inequality should consider the role of housing regulations in funneling income towards the wealthy.

In summary

The developed world is in the grip of a massive, multi-decade housing crisis, which is exacerbating other social and political issues. Many people are very concerned about directly working towards social justice, but I honestly think that the single best thing you could do for minorities and the poor is to make it financially viable for them to live in good communities near good jobs, and prevent the entrenchment of the wealth of landowners. There’d also be a lot less negative sentiment about “immigrants taking our jobs ” with the employment boom that would result from relocation being affordable. These effects are not just economic, but directly affect people's relationships and happiness. The housing crisis is even harming the environment, since detached suburban homes with long commutes are the least eco-friendly type of housing.

But it doesn’t have to be this way! South Korea, Germany and Japan have all kept house prices low, and not through lack of demand either. Landowners in Japan have the right to do practically whatever they want with their property - and so in Tokyo alone more housing units are started in a year than in all of California or all of England. This in a city where there’s barely any empty land left! By good luck or good planning, a few countries have demonstrated that the biggest problem facing modern cities is eminently avoidable. The rest of us need to follow their lead.

- Airbnb

- Too much immigration

- Too little immigration

- Universities

- Transport

Some argue instead that improving transport isn't a substitute for increasing housing density, but a prerequisite for it, because otherwise transport systems will be overwhelmed. I don't know enough about transport infrastructure to evaluate this thoroughly, but it seems odd to me because if people live further away and commute in to city centers, that surely creates even more congestion, especially at peak hours. Living centrally allows more sustainable alternatives like biking or bussing - and with increased wealth from bigger populations, central city governments will have more money to sink into capital-intensive forms of transport like trains and metros.

- Something else?

As this article eloquently argues, it seems like prices are increasing massively in a variety of areas, from healthcare to education to housing. While Baumol's cost disease is often cited as the underlying cause, it doesn't seem to explain the whole phenomenon. Perhaps housing prices are just one part of a bigger trend which is caused by something entirely different. But that seems fairly unlikely to me, because there's a simple chain of cause and effect from all the factors I've outlined above to the increasing unaffordability of housing.

Other effects

So far, I've mainly talked about the financial and economic harms of the housing crisis. But because housing is such a foundational part of our lives, it also has flow-on effects in many areas.

For example, housing startup Zillow found that over the last five years, the average age of first-time home buyers in the US rose by 2.7 years. This is an incredibly sharp increase which turns out to be correlated with a significant decrease in birth rates. That is, the more house prices in an area increase, the fewer children its residents have. While this relationship hasn't been proved to be causal, it suggests that house prices are disrupting people's ability to even have the types of families they desire.

Another metric which has been rising is commuting time, as people need to live further and further away from city centres. Unsurprisingly, this turns out to be strongly correlated with unhappiness and anxiety. People with long commutes are less satisfied with their lives and feel like their daily activities are less worthwhile.

What else affects happiness? Possibly the biggest single factor is quality of social relationships. With higher housing prices, though, it's more difficult to find accommodation near your friends, because you're all much more financially constrained. Increases in the proportion of people renting are also detrimental to relationships: because they move around frequently, renters find it harder to build up deep ties with neighbourhood communities. These are likely factors driving the current loneliness epidemic.

Lastly, you may have heard of Piketty's book Capital in the 21st Century, which argues that the returns to capital are increasing, leading to the rise of a new rentier class at the expense of workers. But this reanalysis argues that when depreciation is accounted for, the only type of capital whose returns are rising is housing! So any discussion of rising inequality should consider the role of housing regulations in funneling income towards the wealthy.

In summary

The developed world is in the grip of a massive, multi-decade housing crisis, which is exacerbating other social and political issues. Many people are very concerned about directly working towards social justice, but I honestly think that the single best thing you could do for minorities and the poor is to make it financially viable for them to live in good communities near good jobs, and prevent the entrenchment of the wealth of landowners. There’d also be a lot less negative sentiment about “immigrants taking our jobs ” with the employment boom that would result from relocation being affordable. These effects are not just economic, but directly affect people's relationships and happiness. The housing crisis is even harming the environment, since detached suburban homes with long commutes are the least eco-friendly type of housing.

But it doesn’t have to be this way! South Korea, Germany and Japan have all kept house prices low, and not through lack of demand either. Landowners in Japan have the right to do practically whatever they want with their property - and so in Tokyo alone more housing units are started in a year than in all of California or all of England. This in a city where there’s barely any empty land left! By good luck or good planning, a few countries have demonstrated that the biggest problem facing modern cities is eminently avoidable. The rest of us need to follow their lead.

The basic premise that expensive housing is bad and largely caused by scarcity of supply is a valid one, but there are a few points I’d like to address.

ReplyDeleteFirstly, while I agree that zoning rules are generally counterproductive, some regulations are definitely needed to stop cities becoming horrible places to live. Secondly, you argue against long commutes, but cities that are really strapped for space like New York and San Francisco could benefit from high-speed rail connections bringing satellite towns into their orbits, as has been achieved in China. Crossrail should likewise provide some alleviation of London’s problems. You also argue that denser cities are better for energy use, yet against the green belt, which encourages greater density of housing.

This brings me to the green belt issue, which is a particular bone of contention – I think the term ‘green noose’ is unfairly negative. You say that intensively farmed agricultural land is actively harmful to the environment, which is often true, but at the same time we do need to produce food somewhere and the green belts contain some of our most productive arable land. They also contain a disproportionately high percentage of our native woodland, which is sadly a very rare habitat, the UK being one of the least wooded EU member states (see here: http://www.surreytreewardens.org.uk/englandsmostwoodedregioninventory.pdf). Many Londoners like to travel to the green belt for weekend country walks and other leisure activities and appreciate it not being further away. I don’t believe we’re seduced by the mere use of the word “green”. Finally, I think the 1% of green belt land figure is misleading, as additional space would be consumed by the infrastructure needed to support the additional housing. Clearly some land must be developed for more housing, but to abolish the green belt would be very damaging.

Next, protection of historic buildings is not absurd and is important to prevent incidents like this – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Firestone_Tyre_Factory – or on a more serious scale the kind of ravages many cities in Eastern Europe suffered under communism, with deleterious effects on their characters to this day. Only ~2% of buildings in England are listed, which is not very high when you consider the number of old buildings we have. While special permission is required to modify them, it does not prevent many being cherished homes. I’m with you on zoning and parking requirements, though I’m sceptical that the Carfax rule has much effect on housing (plus New College seem to have got permission to violate it anyway).

Finally, the fact that so many housing units are started in Tokyo is partly a reflection of the peculiar popularity in Japan of prefabricated homes, so is something of an illusion, and I would argue that replacing houses every 30 years is extremely wasteful (though fortunately this is starting to change: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/nov/16/japan-reusable-housing-revolution). Being able to do what you want with your property may be nice for property owners, but is not so nice for neighbours or the environment – historically Japan has been really bad on sending waste to landfill or incineration. It is also unsurprising that Japan doesn’t have a housing crisis since its population is declining (which isn’t such a bad thing).

I know I’ve made a lot of criticisms, so what can be done? One thing that we really need to do in the UK is rebalance our economy geographically so that it’s more attractive to live and work in cities with room to expand (and revitalise dilapidated former industrial areas) in the north and midlands and thereby reduce the inexorable migration towards London. We could abandon the stupid Heathrow expansion plans and make Birmingham a national transport hub for example. We could invest in centres of excellence for particular emerging technologies. And so on. This would offer people a better quality of life than cramming into an ever more crowded London. As you mention, a renaissance of government home building would also be beneficial.

Hey, thanks for the comment! Many reasonable points, although I still disagree with most of them :P

Delete"Some regulations are definitely needed to stop cities becoming horrible places to live."

I think a lot of what makes good communities happens organically, which is unintentionally prevented by zoning regulations. For example, having residential-only zones promotes car use and means residents don't have shops and cafes as community hubs.

"Secondly, you argue against long commutes, but cities that are really strapped for space could benefit from high-speed rail connections bringing satellite towns into their orbits."

I argue against commutes that take a long time, but I'm skeptical that high-speed trains actually shorten commutes very much, given that the faster the trains go, the fewer stops they have, and so the longer it takes to get to and from the station at either end. They'd still be better than the current situation, but by no means not my ideal solution.

"You also argue that denser cities are better for energy use, yet against the green belt, which encourages greater density of housing."

The green belt is meant to encourage greater density, but in practice, since housing density is so regulation-limited within it, it actually encourages lower density since people end up commuting from outside it. I think that the only encouragement to greater density which is necessary is just allowing the construction of dense apartments (and preventing American-style inner-city slums).

"We do need to produce food somewhere and the green belts contain some of our most productive arable land."

Yes, but just outside London is the worst place to produce that food. Your other points about the Green belt are arguments against abolishing it, but not against using 1%, or 5%, or even all 37% of the land that's currently used for agriculture, for housing instead.

On protection of historic buildings - this is probably a philosophical difference, but I see very little artistic merit in most 20th century buildings, and if others disagree then they're welcome to donate whatever is required to purchase them and/or maintain them as nonprofits, as happens for most of the really striking buildings from the last millennium (churches, etc). In fact, if I were about to build a factory now I'd make it as ugly as possible so that I wouldn't lose control over it in a few decades (although this didn't work for the brutalists :P).

"Finally, the fact that so many housing units are started in Tokyo is partly a reflection of the peculiar popularity in Japan of prefabricated homes, and ... extremely wasteful."

Actually, I also don't have much of a problem with landfill, there's plenty of unused land or abandoned mines to go around. But you're right that this is an outlier - although I think it's still valuable as an example of what's possible on one extreme (which we're nowhere near).

"One thing that we really need to do in the UK is rebalance our economy geographically "

I agree that the government should fix its bias towards London. But I'm not optimistic that rebalancing the economy is feasible without harming productivity. It seems like a major lesson from the last 30 years or so has been that information technologies, which promised to reduce the tyranny of distance, actually create even greater local network effects - hence why SF and NY and LA and London and Paris and Hong Kong and Shanghai are more dominant in their respective specialties than ever. My guess is that it's because we're moving to an economy where the winners get an even greater share of wealth, and so any tiny advantage from location is immensely valuable, and worth the increased costs. But this is something I need to think about more.

Yes. I am looking for a house and am extremely angry right now. Some days I want to scream!

ReplyDelete